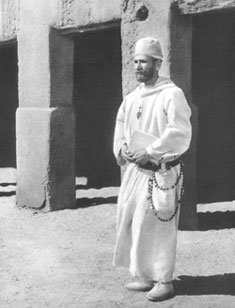

SAINT CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

10. Domestication Tours (1902-1905)

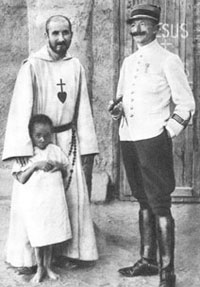

MONK AND FRENCH OFFICER.

Whilst Father de Foucauld is wholly engaged in a purely spiritual apostolate as a cloistered monk, the French Army is pursuing its task of pacification, liberation and civilization. It is a moment of glorious and rapid colonial expansion, and it is certain that without the Army having the upper hand over the southern territories, Foucauld could not have stayed three days at Béni-Abbès.

We have seen how he was welcomed by Captain Regnault and his men. The Father converses with the officer on intimate terms, the fruit of their common convictions, both religious and colonial. He owes great gratitude to this «soul with whom he is most united». «We see things in absolutely the same way», he wrote to Henry de Castries.

The two of them pore over the map and, in March 1902, Regnault, with fifty native horsemen, set out towards the West to explore Tabelbala in an attempt to open a passage to Morocco. Father de Foucauld eagerly relates this magnificent event to Commandant Lacroix, of the Native Affairs Service of Algiers. But they do not spread the news abroad in case the Government is disturbed by these peaceful incursions into Morocco: they could also create diplomatic incidents with Germany and England.

Father de Foucauld writes to Henry de Castries to tell him of the strategic interest of Tabelbala and of the need to conquer this point in order to pacify the whole region (letter of the 13th April 1902). For the service of God and of souls, he reawakens and combines his knowledge as an explorer and his strategy as a high ranking officer. He adds that a post ought to be established there, changing the name of the oasis, so as not to upset anyone in Paris. We see that the Father does not hesitate to confront the authorities, whom he knows to be timorous! He immediately writes to Bishop Guérin asking for permission to follow the soldiers, despite his enclosure, in the event of their succeeding to penetrate Morocco. He recounts how the village chief has told the French that he is expecting them, because they bring with them peace, prosperity and sure protection.

On the 7th May 1902, the glorious battle of Tit, under the command of Lieutenant Cottenest, opened the Sahara to French penetration by putting a rezzou to rout. The whole Targui people surrendered following this magnificent feat of arms!

with Captain Susbielle.

Foucauld spoke of this feat with admiration and deplored the fact that the victory was not exploited and that the rezzou was left to re-form and spark off a sort of holy war in the months that followed, between May and August 1903. Through his conversations with the poor desert people, he knew what was going on and could see danger ahead, right up to the 23rd August when two of our soldiers let themselves be captured at El Moungar by a rezzou of 9,000 people coming down from Morocco, 3,500 of whom were warriors, who killed 40 of our men and wounded others. Lieutenant Susbielle was warned of this and arrived post haste and succeeded in scattering the rezzou. Again, they re-formed and besieged the oasis of Taghit where Captain de Susbielle held out until the rezzou became discouraged and went away.

It is then that the apostolic heart of Father de Foucauld prompted him to work as a priest among the soldiers. Covering a hundred and twenty kilometres on horse, he caught up with them.

For Marie de Bondy, with whom he does not normally talk about these matters, he draws the lesson from these battles:

«This should enable us to get our hands on Morocco. There is the fact of war, which should be the justification for a rapid counter-attack.»

It is the French officer who is speaking, but no less the protector of the poor. In a letter to Henry de Castries, he will state forcefully:

«You ask me what I think about the Saoura-Zousfana events, in 1903... The attacks on caravans, convoys and the surprise attack at Moungar seem to me to be the result of our extremely weak policies around Figuig. For years there have been constant attacks on sentry guards and small detachments around Figuig. Seeing us so easy-going, they acted like a horse winning hands down and have attempted even more serious attacks, which, moreover, are so alluring for these Berâbers, these very warlike Ouled-Djerir, these Châamba rebels!

« The attack and the siege of Taghit has a quite different cause: it is a question of a holy war. A sheriff of Métrara, Moulay Moustapha, preached a holy war, probably for personal ambition, and threw 9,000 people, men, women and children, including 4,000 warriors, onto Taghit...

« Susbielle’s defence of Taghit with only 300 to 350 rifles, and from an extremely bad position, is one of finest feats of arms in the history of Algeria [...]. Farewell, my very dear friend; may Jesus give you His joy and His peace.» (Lettres à Henry de Castries, 27 February 1904, p. 150)

We are going to see this religious man of God, this saint, recover all the qualities of his rich nature and lovingly place them in the service of the poor. Such is the incarnation. The Berâbers, the Châambas are fearsome warriors who can only be subdued by force. Later, he will be able to make friends of them, but for the moment it is necessary to fight them for they ceaselessly raid the oases, robbing the crops. And that, they do every year beneath the complacent eyes of the French who remain inert: that is not acceptable!

But for all that, he has not gone over from religion to politics. This defence of the poor did not interrupt his work of prayer, meditation and adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

BY THE BEDSIDE OF THOSE WOUNDED AT EL MOUNGAR

He stayed three weeks with them, devoting every moment to them, by their bedside, except for when he said Mass, very short meal breaks and the bare two or three hours a night, which he always spent on a sheepskin.

One cannot imagine the moral and physical influence he exerted on these forty nine old stagers of the Legion, little accustomed to things of religion and its ministers. I was not present when the Father first made contact with his new flock; but when I asked him, on the first day of his arrival:

« Well then, Father, what sort of reception did our wounded give you?

- Ouf! he answered with his gentle voice and just a twinkle of mischief in his dark eyes, it takes time to get acquainted; it will come, and I’m very happy to be with them.»

In fact, it did not take long for him to conquer them all with his gentleness, his constant devotion to them and his affability. When he entered their rooms, they seized him for themselves; whoever was the first to have him by their bed (if the grass bunks they lay on can be called beds) would hold on to him the longest, despite the recriminations of the others. The Father was indefatigable: he would write their letters, give them encouragement and chat to them at length in a low voice, and gradually, he would speak to them of God and of religion. One of them in particular, of German origin, with a very troubled past, now seriously wounded in the chest and practically condemned by the Station doctor, gave the Father quite a poor reception at first. After a few days, he could not do without him, and, like all his comrades, the Father told me, he made his confession and received Communion.

The moral influence exercised by Father de Foucauld contributed for many, in the estimation of the military doctor himself, to their recovery. Only one out of the forty nine succumbed to his injuries. Given the state of these unfortunate men on their arrival at Taghit, it was an amazing result, which must be atrributed not only to the care and devotion of the Station’s military doctor and his makeshift nurses, but also to Father de Foucauld, although, in his humility he would not agree. He even accused himself of not having done enough for his poor wounded.

Father de Foucauld’s three week stay at Taghit stays in my memory as an example of the power of the religious devotion of a priest of that stamp.

When he was certain that his presence was no longer necessary and that the doctor could answer for the recovery of the wounded, the Father decided to return to his hermitage at Béni-Abbès. The wounded did not want him to leave. But their pleadings and ours were to no avail.

During his stay, I had obliged him to take his meals with us, and I had seated him on my right, in order to serve him and to see that he fed himself properly, for he had great need of it. To begin with, he refused to serve himself from the same dishes as ours, and so I said to him, half jokingly and half seriously:

« Father, everyone here obeys me ; you will do the same as everyone else.»

Which he did with a smile [...].

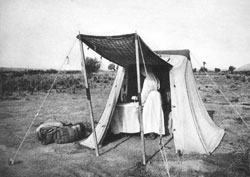

During his stay at the Taghit Station, early every morning, before devoting himself to the wounded, the Father would say his Mass beneath a little canopy I had arranged in the form of a makeshift chapel, on the small portable altar he always took with him. At the beginning, only two or three would be present; then gradually the number grew, and the last Sunday before his departure nearly all the French at the Station, even the “Joyeux” from the African battalion, though not regular church goers, filled the chapel. The priest reminded us all of our youth, our family, of France and of God.

(Gorrée, Les amitiés sahariennes du Père de Foucauld, t. II, Témoignage du Général de Susbielle, p. 109-111)

AGAINST SLAVERY.

At Béni-Abbès, Father de Foucauld did not hesitate to oppose the State, the administration and even some French officers over very important matters. For example, we have seen from the outset how he freed slaves. The enslavement of the Harratins he found absolutely unbearable, as contrary to the Gospel as to French constitutional Law. But in this French territory of Algeria, the incredible thing is that slavery was tolerated. So, he is going to protest. On the 15th January 1902, he writes to Henry de Castries:

«The greatest wound affecting this country is slavery. I had believed until today, after what I thought I had seen in Morocco and heard about in Algeria and in the East, that slavery among the Muslims was quite mild. Now that I talk every day on familiar terms with many slaves, outside the presence of their masters (there are relatively few in the ksours, where the population is quite hard-working, but they abound among the nomads as a consequence of their idleness and pride; for the same reason they abound among the zaouias), I see how wrong I was: Excessive work (drawing water to water the palm trees), the stick every day, no food or clothing, and if they are tempted to flee - which is frequent - they are pursued with rifle shots, and if they are brought back alive, they are mutilated for the rest of their life, being crippled in both legs...

« What is particular about slavery in this country is that, having driven the slaves to do the necessary daily work of use to them, the master leaves them to roam around for the rest of the time in order to find food as best they can...

« There is no other remedy for this shame, for this injustice, than emancipation : emancipation will make no perceptible difference in the ksours, except for the big marabouts. The nomads, however, will be obliged either to correct their idleness and their pride - which would be a good thing - or else have monthly or yearly servants, instead of having slaves - the more probable solution, and very simple...

«The marabouts and the nomads will doubtless find it disagreeable to see the end of the present regime, but the end and abolition of this regime is necessary in the first place because it is a matter of law and justice; and then, emancipation will bring a great increase in the country’s prosperity, for at present the slaves work as little as possible (why work when the master takes all? And whether they work or not, they still have nothing, not even to eat), and the ksourians do not have as much work as they would like (the slaves do some): with the end of slavery, all the slaves will work since work will become their daily means of remuneration. The ksourians will compete with the slaves and will work more, and in the end a few Arabs may start to work themselves...

«It is a shameful immorality, to see these young people stolen, four or five years ago, from their families in the Sudan, to be held here with their masters by force, with the complicity of the French authorities who thus support the effects of these abductions, riveting the irons of these poor unfortunates... There is no economic or political reason that can allow such immorality, such injustice to continue... I earnestly beg you, dear friend, you who are in a position to do something about it, to make known the fact that slavery is publicly permitted and practised on French territory, and I urge you to do all in your power to see that it ends. This question of slavery seems to me to be by far the most serious problem in these regions right now. After that, it will be necessary to instruct, to bring relief, to develop work, so that we ourselves may be blessed by our goodness.» (ibid., p. 118-120)

Father de Foucauld repeats his pleas. At the same time, he writes to Bishop Guérin and to Dom Martin. Through friends, he has the matter raised in the Chamber of Deputies! Finally, Father de Foucauld will win his case in 1904.

He also protests against the sending of discipli-nary battalions, made up of ex- convicts, the “ Joyeux ”.

« One of the greatest defects in our occupation of the South is the use in certain posts (such as Béni-Abbès, Taghit, Igli, etc.) of African battalion companies... Whilst the officers of the Arab bureau work hard through goodness and justice to earn the esteem of the natives, these unfortunate “joyeux”, openly practising every conceivable vice, bring contempt down on the French and on France. They should be confined to the Khreider, to Méchéria and such like posts, far from the native population and kept hidden so that no one sees them... They are not as useful as they are assumed to be as skilled workers: two or three Engineers are far more useful than large numbers of them.» (Lettres à Henry de Castries, 13 July 1903, p. 141)

LAPERRINE.

Laperrine was a great soldier. He had a quality of soul superior to that of Lyautey. He was a legitimist from the Béarn, and a Christian. Above all, he got on perfectly with Father de Foucauld, who wrote about him to Henry de Castries as follows:

«The situation of the oases has greatly changed since Laperrine was made commanding superior. Laperrine is very intelligent, very active, of an independent character and absolutely objective. Under him, the oases have made rapid progress and enjoy real prosperity through a blend of force mixed with justice, constant loyalty and great gentleness.» (Letter of the 17th June 1904, ibid., p. 152)

His idea was to consolidate the African Empire block of French West Africa from Libya, the Fezzan which controls the whole desert, as far as the Atlantic coast; from Algiers to Timbuktu and Dakar. When Brother Charles de Jesus settled at Béni-Abbès, Laperrine succeeded in getting the administration to grant him Saharan companies to guard the Méhara, thus constituting the Sahara as an autonomous military zone. He was appointed commandant of the southern territories when Brother Charles was ordained priest, which was truly providential. God arranges every political and human thing for his saint.

Morocco, unfortunately, remained closed, through government neglect. Laperrine marked time and, despite every obstacle, he decided to tour the Hogar massif, which was in urgent need of pacification. He came to Béni-Abbès to ask for Father de Foucauld’s help, but at first he refused.

«Nature is totally against it, he wrote. I shudder, I am ashamed to say, at the thought of leaving Béni-Abbès, the calm at the foot of the altar, and to throw myself into travels for which I now have an extreme horror.»

But he added : « Must I not go at all ? My clear feeling and opinion is that I should leave on the 10th January. » (Letter to Father Huvelin, 13 December 1903 Correspondance, p. 218).

On the 27th May 1903, Bishop Guérin, Apostolic Prefect of the Sahara, entered the hermitage enclosure with Father Voillart. Father de Foucauld is now able to go to confession. The visitors stay five days, and they make plans. Bishop Guérin hesitates: « I regard you more as a Moroccan than as a Targui and I hesitate before seeing you distance yourself from Morocco.»

For his part, the Father notes:

Bishop Guérin «is pushing me towards Morocco, an impulse I shall follow as best I can, but for the moment I see no opening.» (Castillon, p. 327)

In his diary, Father de Foucauld notes precisely the observations made by this thirty year old bishop, in whom he finds a real friend:

«Here are some of the observations he made: the work of evangelisers, in Muslim countries, is not only to take children and try to inculcate them with Christian principles, but it is also to convert, as far as possible, fully formed men. The evangelical seed sown in the souls of children cannot germinate if the milieu in which they live is not prepared a little...

Besides, all souls are made for the light, for Jesus; all souls are His heritage, and none, with good will, is incapable of knowing and loving Him. The Muslims, therefore, are in no way incapable of being converted... Let us work hard at the evangelization of men of ripe years, firstly through conversations mentioning only God and natural religion, then according to circumstances, giving each one just so much of the truth as one hopes will be acceptable.

«Alongside fixed establishments, it seems that the development of Christianity in these countries demands missionaries who are constantly on the road, spending a few days in each place, returning often, constantly making themselves conspicuous, talking without cease, and doing the work of the apostolate with these people through conversation, through teaching the truths of natural religion first, and then other truths when the occasion arises.» (June 1903, Anthologie, p. 344-345)

The Bishop finally consents to his departure, then he leaves:

«I felt myself to be alone for the first time for many years, Father de Foucauld will write to him, on Monday evening as you gradually disappeared into the shadows. I understood, I felt that I was a hermit... then I remembered that I had Jesus and I said: “Jesus, I love You.”»

Father Huvelin also approved: « Follow your interior movement; go where the Spirit pushes you. It will always be the solitary life wherever Jesus gathers you to Himself in order to give you to souls...» (5 July 1903, Correspondance, p. 212) A new stage is beginning. He will still practise hospitality and devotion towards souls, but as a nomad. He will leave his enclosure, taking his interior enclosure with him.

FIRST TOUR.

On the morning of the 13th January 1904, accompanied by the negro Paul Embarek, with a camel laden with a “well seasoned portable altar”, Father de Foucauld secretly joins Captain Regnault’s Saharan Company, despite the administration’s formal ban. Laperrine carries on regardless: « That will cause further protests; I have a file for that! Wherever the Father goes, the Touaregs, even the most insubordinate, fall to their knees to kiss his gandoura and to receive his baraka: the marabout!»

On the morning of the 13th January 1904, accompanied by the negro Paul Embarek, with a camel laden with a “well seasoned portable altar”, Father de Foucauld secretly joins Captain Regnault’s Saharan Company, despite the administration’s formal ban. Laperrine carries on regardless: « That will cause further protests; I have a file for that! Wherever the Father goes, the Touaregs, even the most insubordinate, fall to their knees to kiss his gandoura and to receive his baraka: the marabout!»

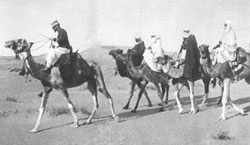

Father de Foucauld, escorted by fifty of Lieutenant Yvard’s infantrymen, undertakes a march which is a feat in itself. He rises before everyone else to say his Mass in the presence of one assistant, whom he has wakened. They start marching very early, at about 4 o’clock in the morning. They march until sunrise. During the march, he remains for the most part on foot and at the back, saying his rosary, his litanies and making his meditation. When the heat becomes overpowering, from 50 to 60 degrees, they stop for the one rest during the whole day. Whilst the men rest, in the overwhelming heat, the Father is indefatigable, visiting the officers and the men, distributing remedies, a little quinine to the feverish. And then they set off again.

He is admired by all. When they halt, the officers and the soldiers are busy setting up the camp, whilst he carries out his civilising mission. He goes from tent to tent, taming these savages, who were conquered only yesterday and subdued by force, giving them remedies and making them little presents: safety pins, needles, small objects they very much need.

For the moment, the Touaregs put up with the French and hate them, and the Father is not unaware of that:

«The natives receive us well. It is not sincere; they yield to necessity. How long will it have to be before they actually have the sentiments they simulate? Perhaps they will never have them. If they have them one day, it will be the day when they become Christians.» (Letter to a friend of the 3rd July 1905, René Bazin, Charles de Foucauld, p. 255)

To Henry de Castries, he will say:

«My little work is progressing... a preparatory work... It is not even I who sow: I prepare the ground, others will sow, and still others will harvest...

«At this moment, I am a nomad, going from camp to camp, trying to civilise, to cultivate trust and friendship... I accompany an officer who has the same civilising mission.

«This nomadic life has the advantage of allowing me to see many souls and to get to know the country...»

(15th July 1904, Lettres â Henry de Castries, p. 156)

On the 2nd February 1904, they reached Adrar, the most southerly outpost, where Commandant Laperrine installed Father de Foucauld with him. Half of the Targui people had already surrendered. In the coming months, he would try to extend French penetration as far as the Sudanese frontier. Laperrine wrote to Captain Regnault on the 19th February that he hoped to let the Father loose among the Touareg at Hoggar, in order to begin a civilizing work by befriending Moussa ag Amastane, their chief.

Constantly repulsed by the Arabs, these people should prove to be less rebellious than others to Christianity.

«The more I see the natives, he wrote in his diary, the more I shall be known by them and so gain, I hope, their trust and their friendship... Giving remedies, occasionally grain and vegetables and, when necessary, alms; that, according to Commandant Laperrine and the widest information, is the way for me to enter into relations with them; but above all learn their language: the best place to study the Touareg language (tamahaq) is Akabli where all the inhabitants speak it and where there are endless Touareg caravans. It has therefore been decided that I make every effort to study Touareg there until, in a few weeks time, Commandant Laperrine can fetch me to follow him on his rounds.» (Castillon, p. 342)

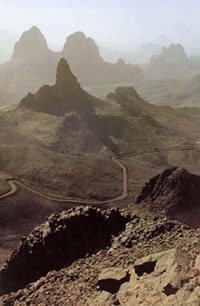

Lieutenant Besset took the Father to Akabli. There he found Laperrine, and together they went down to Timbuktu. During the journey, he drew sketches and continued to learn Tamahaq. They nimbly skirted round the Tanezrouft, the desert of thirst. It was a very tough expedition, during the month of March 1904. They were seeking to make the link between Algeria and Sudan, the dream of all the colonials. This Saharan Company, commanded by a French officer, with the “ Christian marabout” at his side, is truly France and the Church hand in hand, colonising with a view to conquest, pacification and conversion.

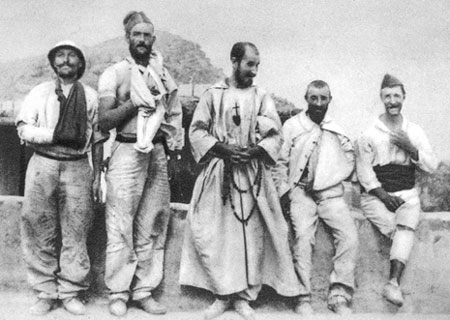

of the camel mounted cavalry.

But at Timiaouine, just as they emerged from the Tanezrouft, there was drama. On the 16th April 1904, the column struck against another French column, coming from the Sudan, under the command of Lieutenant Théveniaud. The lieutenant would not tolerate a column from Algeria encroaching on his territory. Each one defended the expansion of his own military region. Laperrine, who knew that the colonials from the Sudan were capable of every violence, magnificently gave way and withdrew, even though his pride was terribly ruffled. Foucauld approved and refused to shake hands with the officers from the Sudan.

«What I see of the officers from the Sudan saddens me: they seem to be looters, bandits and buccaneers. I fear that this great colonial Empire, conquered for some years, and which could give rise to so much good, moral good, may presently become a source of shame for us, it will give us occasion to blush before the very savages, and will cause the name French and, alas, the name Christian to be cursed, and it will make these populations, who are wretched as it is, to become even more wretched.» (Castillon, p. 350)

«Since their arrival among the Iforas, they have plundered, raided, ill treated and robbed wherever they go. At any rate, their banditry makes me blush before the Touaregs. Having been well received by the Iforas, who welcomed them as submissive tribesmen, bringing them presents and diffa, they acted like savages. Every minute, we learn of a new act of brutality or theft. After having given them a brotherly handshake on their arrival, I shall leave tomorrow without even greeting them farewell, for I do not wish to be part of such infamous behaviour. Commandant Laperrine, unable to allow his charges, the Iforas, to be plundered and maltreated before his eyes and without defending them, having no hope of seeing Captain Théveniaud’s raids end, despite his repeated efforts, and unwilling to defend his charges by taking up arms against his fellow Frenchmen, he decided to retrace his steps and report this to superior authority as soon as possible.» (Diary, 16th April 1906, Anthologie, p. 357-358)

They turn back, thus renouncing the glory of an expedition which, would have linked, for the first time, the North to the South of France’s vast African Empire! They went northwards, passing via Tamanrasset, but they did not stop there. The Father went as far as In-Salah and Ghardaïa, visiting more than three hundred villages.

On the 10th November 1904, he is at Ghardaïa, where he sees Bishop Guérin and hands him a copy of his translation of the Gospels into Tamahaq. From the 25th November to the 12th December, he follows a retreat, taking resolutions on the forty articles of his Rule:

«The value of our works is that of the interior spirit animating them. Our works are only of value in so far as they are works of grace, of the Holy Spirit, of Jesus.»

«It is when one suffers the most that one is most sanctified and sanctifies others the most. “If the grain of wheat does not die, it yields nothing, ... When I am raised up from the earth, I shall draw all men to Myself.” It is through His divine words, not through His miracles nor through His benefits, that Jesus saved the world; it is through His Cross: the most fruitful hour of His life is the hour of greatest abasement and dejection, that when He is most crushed in suffering and humiliation.»

Our Father received a moving testimony of this retreat at Ghardaïa (inset, following page) during the first few days of our foundation, after he had just settled in at Villemaur.

On the 24th January, Father de Foucauld is back at Béni-Abbès, happy to be in his hermitage again. He is tired; he suffers from headaches, and hopes never to travel again.

LETTER TO MADAME REGNAULT

Béni-Abbès, 16 March 1903

Madame,

How much I thank you for your pious letter and for the touching image accompanying it... May the HEARTS OF JÉSUS AND MARY make us like them! May we, like Them, serve, glorify and sanctify their names as best we can!

The Divine JÉSUS may perhaps give you, as well as your dear husband, an occasion to glorify Him greatly, a great opportunity such as is only offered to the privileged: I mean the fulfilment of the possible, probable voyage your dear husband will make towards the South-West. If this voyage is carried through, as I hope, it will in fact be a great step for the establishment of the reign of the Sacred Heart in these regions where Satan has reigned as master for so many centuries - your dear husband will greatly glorify JÉSUS in fulfilling this voyage, and you by praying for the success of this undertaking... If my Bishop wills, and if your good husband authorises me, I shall accompany him. If I do not accompany him, I shall stay here at the foot of the Most Blessed Sacrament, praying for him and for the success of this voyage which I so greatly desire for the glory of JÉSUS and the establishment of His reign. Were I to remain here, I would write to you every week to keep you informed and to allay your worries... But there will be not the slightest worry; accompanied as he will be, he can circulate the entire Sahara without danger; and his provisions are such that his health will not suffer as a result.

In my opinion, it is most desirable for the propagation of our Holy Faith and for the extension of the reign of JÉSUS that this project be carried out - let us pray together so that if this is the will of JESUS, as it very seems to me, your good husband may have the merit and the joy of doing that.

I am awaiting daily the answer from my Bishop telling me, yes or no, whether I should beg your dear husband to take me with him.

How good it is, Madame, to work for JESUS, to enter into His work, to move ahead at His word, at His voice: «Go into the whole world and preach the Gospel to every creature...» What horizons are opening! With what peace the eye rests on these spaces which open simultaneously onto the earth and onto the infinite horizons of eternity and of the divine perfections!... May your dear husband through this work of reconnaissance, and you, through your holy prayers, work with all your might and all your heart to make the Beloved JÉSUS known and loved on this earth, whilst awaiting that both together, you go to enjoy Him in the homeland of eternal love and eternal clarity.

I thank you with all my soul for your prayers. Please continue with them, I beg you. I too pray for you as best I can every day: It is as though Captain Regnault makes you present here at Béni-Abbès; you are present in spirit in this little chapel, before this tabernacle, which you would visit so frequently if you were here; your charming lamp is in front of the tabernacle, representing you... More than ever I pray for you, for more than ever I am with you, for this voyage of your dear husband’s is dear to both our hearts.

May the will of the Beloved JÉSUS be done! May it be done in us and in all! May His Kingdom come! May His will be done on earth as it is in Heaven! Amen.

You can be absolutely certain once and for all that I shall always keep you informed of what is of interest to your dear husband: Thanks be to God there is nothing but the best news to be given of him. Since his return from France, he never ceases to be in the very best of health.

With all my heart, I thank your dear children for their good prayers and their good wishes, and I too send them my fondest love...

Please excuse, Madame, this scarcely legible letter, but I beg you to believe that I am your very respectful and religiously devoted servant in the Sacred Heart of JESUS.

Brother Charles de Jesus

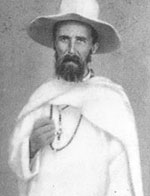

DECEPTIVE LYAUTEY.

to Father de Foucauld.

« Let us hope that the [Moroccan] frontier will totally fall and that the Maghreb will belong to France and above all to Jesus», he had written to Henry de Castries on the 16th December 1902 (Correspondance, p. 136).

On the 28th January 1905, General Lyautey paid him a call to obtain detailed information about his tour of the South and especially to question him on the subject of Morocco. They spoke at length, but what differences there were between them! They met several times more, but Lyautey never pronounced the word Brother Charles de Jesus was waiting for: «Come!»

«Send me a telegraph, he said to him, and I shall come.»

But no telegraph ever came. Their ideas of colonisation were quite different. Our Father wrote two pages on this subject, which we must re-read (see below)

Father de Foucauld wrote to Bishop Guérin on the 20th February:

«He will do nothing for the missions, and nothing against them either. Very gracious and benevolent towards us, treating everyone the same, holding the balance equal, loving the missionaries for their civilizing work, but on one condition: that he does not have to be concerned with them, that he does not hear about them, and that they do their work discreetly and quietly without any need for intervention.» (Castillon, p. 359)

Furthermore, Lyautey is jealous of Laperrine: «General Lyautey, he wrote to a friend, finds that I am much too concerned with the Touareg and has asked that I be thrown out. He has not answered my letters and he has been talking for three days with Gautier (Herr Professor at the oasis hotel) on the following theme: he adores me, he loves me greatly, he finds me perfect, but he does not want to hear about me.» (Castillon, p. 386)

On the 1st June 1908, Father de Foucauld will tell Bishop Guérin of his great disappointment: «If I had been called to go on the Moroccan expeditions [begun in 1907], I would have left the same day and I would have covered a hundred kilometres a day in order to arrive on time: but I was given no sign of life.» (Gorrée, Au service du Maroc, p. 188)

LYAUTEY AND FOUCAULD

In his series of conferences on “The great debates of our times” (1976), our Father dealt with the Mission Catholique de la France (CRC no 107. French edition, July 1976, p. 11-12). From the part dedicated to Catholic colonial France, we extract the following two pages:

If one had to illustrate two different spirits of colonisation, the idealistic which ends in catastrophe, turning against both coloniser and colonised, and the realistic, imbued with the Christian spirit, which alone is beneficent and decisive, it would be sufficient to compare Lyautey and Foucauld. Lyautey made a magnificent success of everything, and yet he died murmuring: « I’ve made a mess of my life.» In Morocco he did a wonderful work, yet it is doubtful whether anything is left of it... Foucauld knew nothing but failure and he died alone in a Sahara on the verge of an uprising, yet his life, his ardent faith and his martyrdom will arouse the enthusiasm of generations. In many respects, they are similar. The one born at Nancy in 1854 and the other at Strasbourg in 1858, they suffered from the war of 70, which exalted their patriotism; but before long they both distanced themselves from religion and the French ideal alike. It is the Army that will save them from interior anarchy, after years of uncertainty, disgust and ennui.

LYAUTEY, ANTICOLONIALIST... EMPIRE BUILDER

Let us begin by following Lyautey... a graduate of Saint Cyr, a man with a «consuming ambition» to do great things, to act powerfully, to create kingdoms (Benoist-Méchin, Lyautey l’Africain, Lausanne 1966 page 16). At other times, in moments of religious exaltation, on retreat with the Carthusians in 1875 and 1876, he thought of becoming a monk. But no, action got the better of spirituality, with a secret and perpetual feeling of frustration, which will sometimes make him sob whole nights, at the height of his Moroccan glory...

What action? As a legitimist, he visited the Comte de Chambord in 1883 but, continuing his travels, he was received in audience by Pope Leo XIII who put him off his monarchist loyalism. «Under the charm of Leo XIII, he will rally (to the Republic)», relates Patrick Heidsieck (Cahiers, Charles de Foucauld, 1954, vol. 33 p. 44). The damages resulting from this papal dissuasion are incalculable. On his return to France, the young officer led the life of the garrison, with no taste for « la Revanche» still «queen of France», and with no political convictions either. He joins Desjardins’ Action morale and seems keen on « the social role of the officer», which he expounds in a resounding article of the 15th March 1891. In fact, he is champing at the bit. He reads the rationalists, who destroy his faith in Jesus Christ; the influence of Leo XIII extinguished his monarchism. The “moral” and “social” spheres are too nebulous as substitutes for Religion and Politics, for God and the King, to satisfy him... He regards all European war as fratricidal and destructive; he despises anyone who feels intensely patriotic. He accepts all religions as the same and all races on the same level. His impatience and his rancour will settle before long on the home country, its administration, its bureaucracy and its bourgeois mentality. The home country he detests is not the Republic and its scandals; it is «this old country», it is... France!

In August 1894, he was fortunately sent to Tonkin. At last, he felt that he was alive ! His meeting with Gallieni was decisive. This child of the people, cold, taciturn and timid, is strictly republican and totally unbelieving, whilst being an admirable soldier, a conqueror and an administrator of genius. The two men lead the campaign against the Pavillons-Noirs and pacify these difficult regions, with the rapturous feeling of creating «a new France». After a short while, Gallieni was sent to Madagascar, from where he called for Lyautey. Lyautey gave his full worth in this vast country which was to be conquered, pacified and organised. It was then that he chose his famous motto: The joy of the soul is in action, and enjoyed six heady years of creative freedom!

In 1903, he was sent to Aïn-Sefra, on the Algerian-Moroccan borders, in order to stop the predatory incursions of the Berâber. «The animal of action», as he defines himself, is there, ready to pounce, to conquer in order to pacify, to charm in order to reign and to raise from scratch a great modern country out of this land sunk in anarchy and misery. Paris wants none of it? He detests the slowness and timidity of the Administration... The home country again! He forces the obstacle and carries on regardless!

He conquers Morocco. With the hand of a master. There he gives his full measure, that of one of the greatest conquerors of the modern era, that of a remarkable empire builder. Slowly, he brings about pacification, through ceaselessly constructing roads, ports, schools and also mosques! Alarmed at the dissidence of Abd El-Krim, Paris sends Maréchal Pétain to take command of operations. Lyautey, who would have been sufficient, is sickened by this move. He rebels and resigned in 1925. He was never to return.

He no longer has his Morocco. He no longer has anything. Inaction for him is unbearable. He takes his mind off it for a while by creating this ephemeral Empire, this dream Empire, which was the Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931. Its success was brilliant, like a fireworks display. Then, in increased solitude, he turns again to God and is converted. In 1934, spurred by the indignation provoked in France by the slaughter of the 6th February, he allows himself to be tempted by the other great Adventure, - the adventure he had always dreamed of, if we are to believe his lucid biographer, Benoist-Méchin, and he answers the call of the national Leagues: he will be the Maréchal of the coup d’État that will overthrow the Republic! But he is seized by anxiety. He feels himself to be very much a foreigner in France! La Rocque, chief of the Croix de Feu, his predecessor in Morocco, dissuades him, and he is easily convinced. He renounces this “ action française”, the only action that would have been decisive and up to his true worth! But, from Leo XIII, Albert de Mun, Paul Desjardins to La Rocque, all supporters of the (Republican) regime, he was misled over France and over Religion. Besides, there is no longer time. Lyautey died in 1935.

Did he at least conquer an Empire for France? Did he raise up peoples to true civilization? Not at all! He came, he conquered and he opened markets. But, more like Napoleon than Cæsar, he did not know what it was all for, other than his insatiable pride; nor did he know who these kingdoms were created for, other than for himself. With no religion and no attachment to his home country, his «old country», a finished country, he systematised the views of Gallieni, the republican and unbeliever: that the religions of the conquered countries have to be respected and there must be no desire to give them ours; that the native authorities have to be maintained and are not to be replaced by ours; that native customs and costumes have to be preserved; and that our accursed colonial administration must always be resisted. « Conquer all in order to preserve all» (B.M., 51), at the risk, knowingly and deliberately incurred, of losing everything (Cahiers, p. 71). Do nothing for France.

Prefer the PROTECTORATE, which does not bind peoples to us, to the COLONY, which tends towards assimilation. And prepare for our departure at the same time as our conquest! For they are in their own home, and we are only there for the glory of serving them, for the honour of having helped them! In 1930, Lyautey the African, is ever angry at the sight of Frenchmen coming in large numbers to settle in Morocco, his Morocco. It does not belong to them, he roared!

He did not work for France. Did he work for Morocco? The oblivion and the void into which he will suddenly fall will demonstrate the vanity of his glory. Independent Morocco will not even keep his remains on their soil. Unchanged in its Islam, it will have gained from Lyautey only a superficial veneer of modern civilization. Only the naive and the ignorant will be taken in by the Autobiography of King Hassan II, and believe that Morocco is on the rails of civilization! The Christian parenthesis is closed; the occupying Arab administration is corrupt, and the antagonism between Arabs and Berbers remains the cause of ruin and permanent injustice. False religion, vices and primitivism are repossessing that country, as everywhere else in Africa, all because we refused to convert them first and colonise them thoroughly, by attaching them to us for ever as sons, slowly raised by their fathers until they became like us in all things, and for good.

FOUCAULD, FOUNDER OF CHRISTENDOM

The lesson of Father de Foucauld is so different! Lyautey seems never to have loved anyone in the world except himself, and others as a means of his dominance, instruments of his ego: his sister, his officers, his “Team”, in which he saw himself acting, living and creating.

Foucauld, the tender-hearted orphan, had a great friendship for his comrades of Saumur, and it was in order to be with them that he rejoined to the Army in 1881 in the battle against Bou-Amama. The gears of love are set in motion. He begins to love French Algeria through its army exposed to surprise raids, and the little people of the Oranais whom the Army protects from looting. Gifted with a keen understanding of military affairs, he immediately understands that it is essential to conquer Morocco for Algeria to enjoy calm. It is in order to prepare the way for this that he undertakes a clandestine and dangerous exploration of this forbidden country in 1883-1884. And he is moved to hear the Moroccans, who guessed his mission, tell him of their desire for French peace: «When are the French going to come?»

Nearly twenty years will pass, occupied with the things of God, from his conversion in 1886 until he gives himself totally to the greatest Love, that of JESUS. Not a single day will pass, however, without his remembering to pray for his friends of Taza, Tadla, Tisnit and Mrimina, who are waiting for the French and whose conversion he so keenly hopes for. When he is ordained priest, in 1901, and chooses to live as a hermit among the most abandoned of the infidels, it is Morocco that he is thinking of, and he will settle near its southern gate, at Béni-Abbès, awaiting the hour of Providence.

Then Lyautey arrives at Aïn-Sefra in 1903! Foucauld signals to him that he is ready to follow the soldiers, so that the Gospel might enter Morocco in the footsteps of France. But Lyautey will not summon him. Lyautey does not want a «Christian marabout» in his kingdom. This rejection, this indifference is a shocking disappointment today: it is the crime of a great man against Jesus, against France, against Morocco. It is a stain on his glory, which he would not want to see offended by anybody!

Since he is not wanted in Morocco, a country so rich and beautiful which he had only recently judged to be most apt for advancing towards civilisation and conversion, Brother Charles de Foucauld, «the universal brother», answered the call of Laperrine, the Catholic legitimist from the Béarn, who plunged into the Sahara Desert in order to fight the Touareg raiders, subdue them, tame them and win them for France. The soldier monk and the most Christian soldier advanced along the desert tracks to Tidikelt, to Hoggar. What he was unable to do in a big way as part of Maréchal Lyautey’s brilliant success in Morocco, Father de Foucauld will attempt to do in poverty, but heroically, with this modest, ardent-hearted soldier, Commandant Laperrine

Let us do this justice to Lyautey: during his short time at the War Office (Dec. 1916 - Mar. 1917), one of his first decisions will be to send Laperrine back to the Sahara. That was on the 7th January 1917, one month after the assassination of Father de Foucauld. This great judge of men had understood that only Laperrine could hold the immense domain of the French Sahara, at the heart of France’s African Empire, after the disappearance of the Christian marabout.

Foucauld succeeded in nothing. He converted no one. And, the height of derision, those who claim to be his followers, have betrayed his memory and distorted his message. So why is this Memory and this Message still such a strong life force for a great future? Because he loved... Yet he also experienced the disappointment of garrison life, the sad ageing of France under the IIIrd Republic, and the decline of her élite: unbelievers, scientists, liberals. As a Trappist at Akbès in 1895, when 140, 000 Armenians were massacred by the Turks, he was indignant at the inertia shown by the European nations and grieved not to die as a martyr among these poor Catholics left defenceless before Muslim barbarity. He too, under various influences yet to be elucidated, believed in Leo XIII and his “Ralliement”, he took no side in militant politics out of obedience to his spiritual director, whilst groaning and praying at the news of scandals and anti-religious persecution...

But he was guided by Love in all things. He forgot himself for the true good of his brothers, without accepting lies or tolerating illusion. He loved France and wanted to make her loved by all. He loved Jesus and His Church, and from the day he discovers Them, he wanted all the peoples of the earth to love Them with him. He loved the soldiers of the colonial Army and became their priest and father. He loved the poor people of the Sahara and ardently wanted their good. Their well-being was firstly the French peace followed immediately by direct French administration by those officers who will later form that admirable corps of officers of Native Affairs. Because for him no theory held good in the face of the injustice and misery suffered by the poor, he wanted nothing left of native feudalism made up of brigands, liars and oppressors. He wanted a French administration, but noble, generous, just, swift, intelligent, effective, omnipresent and therefore military! But, for love of the poor, he demanded that it be irreproachable!

He suffered from the Republic for its secular, materialist, centralising policies, for its stupidity and inhumanity. Out of prudence, he could say nothing about it. Without the protection of Laperrine, he would have been banished from the Sahara! He was pained by the apparent irreligion of so many Frenchmen, who scandalised the natives and retarded the time of their conversion. More than anything, he detested the master-slave dialectic, under whatever form it took, but he knew that it was possible and desirable for deep, religious, human contact to be formed through relationships between the colonised and the colonisers, based on goodness.

He wanted the «FRANCISATION» of the populations of France’s great Empire, for only that would provide its moral and material progress with a stable background, free from troubles and subversion. But what he meant by «FRANCISATION» was not some empty, pretentious proclamation of equal rights; for him, it was above all a matter of CHRISTIANISING, CONVERTING TO CHRIST these poor pagan or Muslim souls. Without that, nothing lasting could be done and everything would fail: in fifty years, they will throw us out into the sea! And to this warning, he added another, less well known: as long as there is a single Muslim in this immense Empire, France will have an enemy there (read the admirable Pierre Nord’s book Charles de Foucauld, Français d’Afrique, Fayard, 1957; and on the opposite side, Michel Carrouges’ appalling Hegelian work, Foucauld devant l’Afrique du Nord, Le Cerf, 1960).

When the 1914 war broke out, still under the impression of the atrocities against the Armenians and learning of the violation of Belgian neutrality, involving horrible massacres, he bequeathed us his last cry from his Hoggar: it is his Call for a Crusade against the barbarism once again assailing Christendom. These predatory empires must be conquered and destroyed for ever. Then the peoples entrusted to us must be civilized and Christianised under the French flag. The French must come from the Mother Country in large numbers to help lift up the natives of our colonies and gently prepare their conversion, as parents acting towards their children. In receiving so many goods things, the infidels will be attached by indissoluble bonds to the common Country and to the Church who will have been so beneficent to them.

On the 1st December 1916, Brother Charles de Jesus was assassinated, a soldier-monk of our modern Wars, the greatest French martyr of the 20th century. Tomorrow, his call will be answered by Catholic Phalanges who will arise to restore national unity and bring about the federation of Europe in a civilized world and the restoration of a French and Catholic Empire. For God’s battles are not won in distant lands or on the streets, but primarily at the centre of civilization, in the hearts of men... Si Dieu le veult!

Georges de Nantes, La Mission catholique de la France, CRC n° 107, French edition, July 1976, p. 11-12.

SECOND TOUR IN THE HOGGAR.

Convinced that Father de Foucauld is the only priest who can settle in the South, Laperrine begs him to go on another mission, this time with Captain Dinaux, Commandant of the region of Tidikelt. At first the Father refuses, but Father Huvelin and Bishop Guérin persuade him to accept. He sets off again, therefore, on the 3rd May 1905, with Paul Embarek. As far as Akabli, he travels with Inspector Étiennot, responsible for tracing a trans-Saharan telegraph line. «As morally thick as he is physically», this official is anti-clerical, republican, very unpleasant and spends his time making gibes against Father de Foucauld. He is detested by everyone in the column; but the Father gives proof of great patience, using moderation with him as with all. Now, it happened that they strayed, and for a moment they thought they were lost in the vast desert, at a temperature of 55 degrees in the shade! Their supply of water was dwindling, and each one had to drink sparingly from his foul-smelling guerba. Étiennot had drunk his water faster than the others, and swore against God; Father de Foucauld offered him some of his: it was to look for death! The other drank it with disgust, complaining of the smell, so as not to have to say thank you !...

Such was the charity of Father de Foucauld, prompt to offer himself to danger and insecurity in order to convert souls to Jesus, even the most rebellious! During the march, he only agreed to mount his camel at the limit of exhaustion. Most of the time he followed on foot, at the end of the column, and before long his mended sandals fall to pieces.

When he is not devoting himself to any other pious exercise, he continually recites Ave Marias for the establishment of the universal reign of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. At night, he prays and works. Early in the morning, before the convoy is underway, he says his Mass.

CCR n° 294, March 1997

WITH THE WHITE FATHERS OF GHARDAÏA

On the 30th January 1959, four months after the foundation of our community at Villemaur, in the diocese of Troyes (15 Sept. 1958), Father de Nantes received this direct testimony, alive and encouraging, from Father Louis David, White Father of Ghardaïa, who had known Father de Foucauld.

Ghardaïa, 30. 1. 59

Father

Firstly, I begin by apologising for my delay in answering your letter of the 12. 1. 59; I was preparing a lecture on the history of the M’zab, which I have to give to the rural centre of Ghardaïa about now... My audience will consist of Mozabites - our future parishioners - rather touchy and grumpy people, proud to the point of believing that they alone possess all truth and knowledge. For me, this is a fine opportunity to say that, when it comes to history, we know at least as much as they do.

Sister Marie du Rosaire has told you about me and of my encounters with Father Charles de Foucauld.

I thank God for having been given the chance to enter into contact with a saint. We received him here with us at Ghardaïa on several occasions. The first time the good Father came to M’zab was to pay a return visit to the Rev. Father Guérin, our Apostolic Prefect, for his visit to Béni-Abbès.

Father Charles de Jesus came to us early in November. His sole companion was a native who had to look after the camel, which bore all that was needed by these two men, who were alike in their simple needs. The one was simple because of his primitive education; the other had become simple through being the disciple of the Poor Man of Nazareth.

Before arriving at the Mission our traveller had wanted to tidy himself up a little, so he had had his hair cut and his beard trimmed. We always thought that he had wanted to make himself look ridiculous as an act of humility: his hair had been cut in the form of steps and his beard had been trimmed any old how. From two big bags hung from the sides of the camel, he took out a soutane, that is to say a cotton gandoura, but it was in such a ragged state that it made the wearer look even more ridiculous.

We prepared him his room: his bed was a plank with a cover; there was a wash basin, a jug of water and a big table. He found it all perfect.

For a month, he lived exactly as we live, with no exception, eating everything we offered him. He said his Mass like everyone else, neither too fast nor too slowly. In the evening, after supper, he joined us. We would ask him to relate certain episodes of his exploratory travels in Morocco. He answered our questions with the greatest modesty. It seemed as though he were talking about someone else; he never put himself forward and never exaggerated. When he had answered the question, he would return to his silence like a child who only speaks when he is asked.

When the season of Advent came, he asked our permission to follow his own rule... He kept silence throughout Advent and got on with work from morning to evening. For food, he had asked us to place at his door a loaf of round, flat Arab bread, made with unleavened dough and baked on an earthenware plate made for that purpose. That, and a jug full of water, was all he ate. We wondered how he could keep going on such a diet.

He spent a good part of his night in our chapel, saying his breviary and making his meditations...

Before and after this month of silence, of prayer and of work, he was invited two or three times by the Officers of the Arab Office. For him it was torture: his stomach was no longer accustomed to more substantial food. He accepted it all, no doubt in a spirit of penance and to please his hosts.

He himself told us of an event which illustrates his breadth of spirit. He was travelling between In-Salah and the Hoggar; officers in the Bled, who were chasing after road cutters, learned that he was going to pass through their camp and so decided to offer him a good meal. They sent a goumier to the neighbouring nezla to fetch a chicken, which they prepared their very best. Father Charles did not touch it, with the excuse that he had a stomach upset.

When the chicken was eaten, Father Charles smiled and asked them:

«Do you know what today is?

- We have no idea, Captain Charlet answered. All we know is that it will soon be Easter.

- Today, said Father Charles, is Good Friday.»

Those good men were grieved at having eaten meat on Good Friday. The Father consoled them saying:

«You do enough penance all the year round. Jesus does not begrudge your having eaten meat today.»

Very hard on himself, Father de Foucauld repeated to us on many occasions that if God wanted him to have companions, he had no intention of making them follow the same diet as his.

There, Father, a few features that come back to my memory and which impressed me most.

I pray that Jesus will bless you and the project you have formed to live after the manner of the Little Sisters of Montpellier. There can never be too many contemplative souls in this world.

May Father de Foucauld bless you! Please accept, Father my religious and respectful regards. David.

P.L. David, White Father, Ghardaïa (Oasis)